PATSY SCALA

WHY I BECAME INVOLVED IN COMPUTER-ASSISTED ART: A STUDY IN POETRY AND IMPATIENCE

I became involved in computers, as I became involved in art, through the back door: I have had no formal training in either field.

My work as an artist began with the writing of poetry, and through poetry, I was able to put onto paper feelings, ideas, everything which flooded my head, heart and body. With poetry, however, there was always something missing. As I wrote poetry, and, for that matter, as I did almost everything else I have ever done—drive a car, take baths, have a baby, have sex, teach—my mind was always flooded with visual images as well as verbal images. I had an uncontrollable urge to execute these visual images which constantly filled me.

There was, however, a problem with this. I can't draw. Nor can I paint or sculpt. I would attempt to produce an image in my head on paper, on canvas, and the image would somehow distort itself into a grotesque caricature of what I had wanted it to be.

I finally discovered, however, that through film, I could to some extent reproduce the fast-moving, brilliantly colored images that I saw in my mind, so for a while I worked in film. At this point, another aspect of my personality entered the picture: impatience. I hate to wait for anything, least of all a finished product of visual images I envision. I discovered that by the time I had completed a film, my mental images were very different than what they had been at the time I had conceived the film.

It was at this point that I turned to video, realizing that through this medium I could create images in real time. As I was seeing the swirling colors and movement in my head, I could record them on video tape.

I luckily became the artist in residence at the television studios connected with the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse, and was able to work with two two-inch high-band quadriplex video recorders, two film chains, three broadcast-quality studio television cameras and a highly sophisticated Sarkes-Tarzian control panel with two separate special effects generators. What a trip! I could sit at the control board and compose visual poetry in real time, as I watched my compositions on four color television monitors in front of me.

Even with all this wonderful equipment, however, I felt that something was lacking: truly varied input for my video-graphic pieces.

It was at this point that I became involved with computers. I attended a workshop given by Ken Knowlton at Eastern Michigan University. (I actually went there to go to a video workshop that was being held simultaneously with the computer graphics workshop run by Knowlton, but I discovered that the video workshop dealt mainly with black and white porta-pak use, and that is not my style of video.) So stuck in Ypsilanti, Michigan, having paid my workshop dues, and having nothing to do but explore Ypsilanti, I decided instead to take Knowlton's computer graphics workshop. Reluctantly. Even though I had mastered the control of rather complex video equipment, the mystique of the computer had convinced me in advance that I could never learn to program a computer. I became violently ill, suffered severe stomach cramps, and fought continually with anyone I could find to fight with. Then a miracle happened. Ken convinced me that I actually could make a computer do what I wanted it to do. The rest of my stay in Ypsilanti is somewhat of a blur. My husband tells me that I had an affair with a PDP-10 computer, and he's probably right.

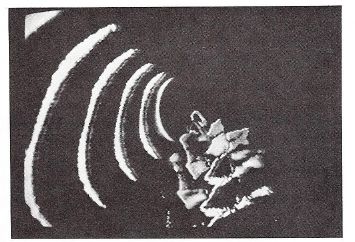

But it opened the door I was looking for: more types of varied images for my video tapes. I began to work with analog computer controlled sinusoidal waves shot on film, then distorted through videographic animation. I worked with my husband in collaboration on works involving computer imagery and video. I am currently in the process of collaborating with Stephen Levine from Lawrence Livermore Laboratory on more video tapes using computer input.

Now that I have discovered the computer, I don't think I will ever go back to other types of input to video, unless the supplementary input is combined with computer input.

My reasons? First of all, my video tapes tend to make a great deal of use of negative as well as positive space, and computer animation lends itself ideally to this type of imagery. Second, since I like images which can rapidly pulse, invert on one another, swirl, and burst out from an epicenter, the computer also lends itself to this type of imagery. Third, since my video art is still very much connected with my poetry, and I strongly believe that video images are a viable language for the writing of purely visual poetry, the computer gives me more options for visual diversity than any other single tool I could possibly use. Fourth, my impatience again. The computer can produce images rapidly, and this is very important to me.

As far as I am concerned, computer art is going to be the catalyst which changes both the art world and the computer community. Once something has been done in art, the art world as a whole doesn't go back—even though some people will always go back to painting portraits of their grandmothers. Now that computers have become an integral part of the work of at least some artists, I strongly feel that other artists will begin to look at the computer as a viable tool for the production of art. At the same time, I believe that computer scientists are beginning to recognize that data they produce for scientific purposes can be quite beautiful. They—at least some of them—are becoming artists.

It could be a perfect melding of the many varieties of persons existing in our highly technological age.

Would I recommend the computer as a tool for all artists? Of course not—no more than I could recommend the paintbrush as a tool in my own art. But I would say that for artists looking for innovative images, artists seeking to find a place in their art for the technology which surrounds us, artists who are not afraid of machinery, the computer is a perfect tool.

Up with computers for artists!

Syracuse, New York

October 1975

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Section | Next Section