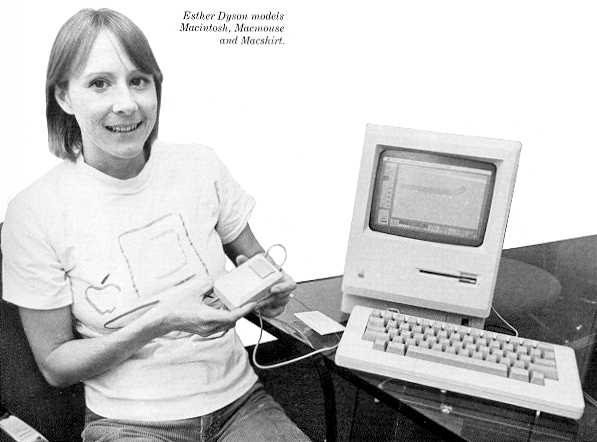

by Esther Dyson

Esther Dyson is president of EDventure Holdings Inc. (formerly Rosen Research) and editor-in-chief of its newsletter, RELease 1.0.

I recently discovered that Apple's Macintosh computer is in fact short skis for the mind.

Let me explain briefly about skiing. The faster you're skiing, almost out of control, the easier it is to maintain your balance. What stumps most beginners is their unwillingness to approach losing control.

In the old days, beginners started on gentle slopes and gradually built up their confidence and skill until they could handle the tough stuff. Then, a few years ago, a new approach came into vogue: the Graduated Learning Method. The idea was to start the user out with short skis, which are more controllable than the two-meter monsters favored by the experts. Long skis give more power and strength to experts who go so fast that the twist of a short ski would have little impact, but they only get in the way of a novice.

Like short skis, the Macintosh may be a little limiting for the experts, but it makes computing accessible to a much larger number of people who are afraid or incapable of using the traditional methods.

If the Mac is short skis, then ski boots are the interface. They are what enable you to control and maneuver your skis; they are what the computer user actually feels, sees and touches. If a boot is too loose, you can't move it precisely; if it's too tight, you'll give up in despair, as I almost did.

One Saturday morning not long ago I went to a ski rental shop in Squaw Valley. The salesman asked me my shoe size and handed me a pair of battered Nordica boots. Of course, the boots didn't fit properly. I tightened them to get a firmer grip, but I still had a hard time getting the skis to do what I wanted. Short they were, but not well connected to my legs.

If they were a computer, I would have said the interface was wanting, like a mouse that skips around erratically. If there's anything worse than being difficult, it's being unpredictable. Mac, on this score, works very well: all the software that runs on it follows the same rules. What's more, Mac is comfortable: no aching ankles, no cold toes ... the boots fit.

I got down the hills, yes, but only slowly, and I didn't have that much fun doing it. The power of the skis wasn't accessible to me. I returned the skis and boots, and found another ski shop. What with better-fitting boots and a friendlier send-off, Sunday went much better. By the end of the day I was jumping over moguls.

In the same way, the Mac delivers a feeling of control and safety that encourages people to try new things. With long skis or a complex computer, you have the feeling that you're operating or maneuvering something. With short skis or the Mac, you feel that you're working with an extension of yourself.

Now, it's not fair to end this piece without mentioning that the GLM method of teaching skiing is controversial-and that it's a learning, not a using method. Do those short skis make it so easy that people never graduate to long skis? Do they enable? Or do they cripple?

One can ask the same questions about the Mac. Yes, it will invite lots of people to use a computer. But are they really using a computer? Will people graduate to a "real," difficult computer, or will they always be stuck at the Mac level, reliant on the Mac's friendly, comfy-boots interface, its consistent commands and its overall easiness? Or does it really matter so long as they get what they want out of their computer?

Here our metaphor begins to break down. Short skis really don't work as well at high speeds, for good skiers. But that's not necessarily true of short-ski computers. Currently, the Macintosh has only limited memory, but that's more of a financial consideration than a fundamental design problem. There's no reason the Mac can't get more powerful without losing its essential character. In fact, the Macintosh uses the power of a high-technology 68000 chip (the same that's inside many $20,000 computers) to make itself easier. It's inherently more powerful than the harder-to-use IBM PC, but its power makes things easier, not tougher, for the user.

Incidentally, when I told Don Estridge, head of the IBM division that developed the PC, that the Mac was short skis, he thought for a moment, then said: "Yes, but tall people need long skis."

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article