THE LABOR FORCE

A true history of the first women in personal computing

by Bonita Taylor

Bonita Taylor is editor of The Buyers

Guide series far Ziff-Davis. She is one of the few home users of the

Xerox 820 personal computer.

The tales of those

inspired pioneers who brought forth the personal computer industry have

always centered only on heroes: a few dozen obsessed males working

brilliantly against terrific odds, in the humble surroundings of

kitchens, basements and garages, nudging their ideas into a

multibillion-dollar reality. Now it's time to credit the heroines.

While no one disputes that men had the primary role

in the conception of the industry, women were the ones who went into

labor. "The women may not have always been the creative driving force,"

says Betsy Staples, editor of Creative Computing. "But they made it

possible to get the men's ideas in the public eye." The women who

worked behind the scenes (and in the basements and garages) helped many

of the newly formed computer companies grow and survive. These female

pioneers provided skills and hours beyond the call of duty and

certainly far beyond what the neonatal companies could have afforded to

pay.

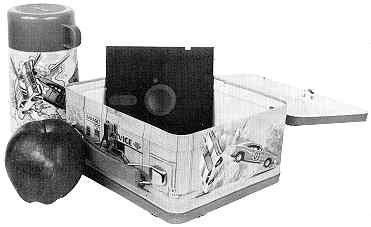

The range of chores to which women were assigned

during this period was extensive. No task was unthinkable. Some of

these pioneers talk about encouraging (bribing?) their children to help

after school. Some remember spending nights in the kitchen with a Seal

a Meal machine, packaging diskettes with one hand and lunchbox

sandwiches with the other. One woman (who wishes to remain anonymous)

recalls the time an extra diskette turned up: some customer, she was

sure, would find a gooey peanut butter sandwich in his package where a

disk should have been.

Off to Market

It's

not simply a case of good women behind good men. Unsung women have also

distinguished themselves by demonstrating their business and marketing

acumen. There's Dorothy McEwan, who in 1975 worked as a customer

support representative for the phone company while she studied computer

programming and fulfilled her responsibilities as a homemaker. The

mother of two, she was married to Gary Kildall, a Naval Postgraduate

School professor who at that time was writing the CP/M program. "He

needed things done, so I did them," Dorothy recalls. "I never thought

about what it would lead to."

It's

not simply a case of good women behind good men. Unsung women have also

distinguished themselves by demonstrating their business and marketing

acumen. There's Dorothy McEwan, who in 1975 worked as a customer

support representative for the phone company while she studied computer

programming and fulfilled her responsibilities as a homemaker. The

mother of two, she was married to Gary Kildall, a Naval Postgraduate

School professor who at that time was writing the CP/M program. "He

needed things done, so I did them," Dorothy recalls. "I never thought

about what it would lead to."

CP/M became the first commercial operating system

software distributed by a non-computer manufacturer as Dorothy, using

her business skills, helped mold and build Digital Research Inc. Today

she is a vice-president of the company, with responsibility for

marketing, communications, customer support, and educational and legal

services. But when the computer press needs a computer pioneer to

interview, the call goes out to Gary, not Dorothy.

Mary Eubanks is another woman whose contributions have been

overlooked. After raising four children, Mary was ready to sit back,

relax and possibly start her own travel business, when suddenly she was

called upon to once again assume the role of supportive parent. Her son

Gordon had written CBASIC, the first microcomputer language to offer

reasonably good structure and commercial mathematics capability, and

had started a business to sell it. But Gordon was also a serving

officer on a strategic nuclear submarine, and it's difficult to run a

software company while sitting on the floor of the Pacific Ocean.

Mary Eubanks is another woman whose contributions have been

overlooked. After raising four children, Mary was ready to sit back,

relax and possibly start her own travel business, when suddenly she was

called upon to once again assume the role of supportive parent. Her son

Gordon had written CBASIC, the first microcomputer language to offer

reasonably good structure and commercial mathematics capability, and

had started a business to sell it. But Gordon was also a serving

officer on a strategic nuclear submarine, and it's difficult to run a

software company while sitting on the floor of the Pacific Ocean.

Mary volunteered to manage the company. "I knew

nothing about computers," she says. "But I was his mother, and I was

determined to hold the business together one way or another." She

dedicated the next few years of her life to Compiler Systems, and

Gordon came out of the Navy to an extremely prosperous company whose

CBASIC was one of the most commonly used languages.

Then there's Judy Goodman, who in the early 1970s was working as

a substitute elementary school teacher, part-time helper in her

husband's TV and stereo shop, and full-time homemaker with three

children. During this time her husband became interested in computers,

which he saw as "the wave of the future." He educated himself and in

1977 wrote a file management program called Selector, but it was Judy

who handled the orders and the marketing (including product

distribution and trade shows) and who was responsible for staying on

top of finances. Today she is vice-president of Micro Ap, with

responsibility for marketing.

Then there's Judy Goodman, who in the early 1970s was working as

a substitute elementary school teacher, part-time helper in her

husband's TV and stereo shop, and full-time homemaker with three

children. During this time her husband became interested in computers,

which he saw as "the wave of the future." He educated himself and in

1977 wrote a file management program called Selector, but it was Judy

who handled the orders and the marketing (including product

distribution and trade shows) and who was responsible for staying on

top of finances. Today she is vice-president of Micro Ap, with

responsibility for marketing.

Cynthia Posehn, who formed Organic Software, Inc.,

recalls that "somebody had to answer the letters and the phone calls,

ship the software and manage the money." In 1977, when her husband

Michael needed a software customization proposal typed up, she was

assigned the task. "I'm a terrible typist," she says, "and it took

forever to get it out." Michael got impatient and decided that a word

processing program was needed. Textwriter was written shortly

thereafter. "His intelligence and drive got the company going," Cynthia

admits. "He placed the ads and made the contacts." But Cynthia did all

the packaging and saw to the printing, as well as anything else that

needed to be done. Today she is the firm's secretary-treasurer,

responsible for the financial, legal and marketing side of the business.

A Man's World

The women in these cameos arrived in the personal computer industry by

accident, but they share similar characteristics. They are tolerant,

determined, competent, hard-working and willing to take on something

new. And they are dependable. They were expected to work on behalf of

the men they knew and to tend all phases of the business. And they did.

Nonetheless, despite the significant contributions

of these and numerous other women during personal computing's formative

years, publicity and credit for the accomplishments of their respective

companies have continued to go to men. "As journalists, we wanted

interesting personalities as well as `names,' " says Maggie Canon, the

editor of A + magazine. "The more famous someone became, the more

interesting that person was to write about. The companies themselves

promoted the men."

According to the National Science Foundation, women

represent 26 percent of the computer labor force. We don't know how

many in this group have made critical contributions to their companies.

What we do know is that the success of the early entrepreneurial

companies shaped the computer industry as it is today. To survive the

early period, each needed not only the ideas contributed by their

heralded entrepreneurs (men), but also the skills of the various

unheralded women.

Would the personal computer industry exist as we know it without

them? "Probably not," says Nancy Lehman, another pioneer. "This society

is not taught to acknowledge what women do and what would happen if we

stopped."

Would the personal computer industry exist as we know it without

them? "Probably not," says Nancy Lehman, another pioneer. "This society

is not taught to acknowledge what women do and what would happen if we

stopped."

It may be that if women are to be recognized for

their achievements, they will have to write the chapters themselves.

This is only the first.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article