AND VILLAINS IN

POPULAR CULTURE

by Terry S. Landau

Terry S. Landau is a psychologist,

paralegal and professional writer. She is a member of the Wolfe Pack.

The movie's story

line goes like this: Bunny Watson (played by Katharine Hepburn) tries

to protect her job and her fiancé (played by Spencer Tracy) from

a clever villainess named Emmy, who appears to have designs on both.

Sound familiar?

But wait. Emmy is a computer. Her real name is

EMERAC and her immense frame occupies an entire room. Despite her

brightly colored lights, she is austere in appearance-particularly when

contrasted to the homey clutter of Bunny's office space in the

reference library of a television network.

Desk Set

(1957) was not the first movie to express the threat posed by

mechanization (Fritz Lang's ominous Metropolis

was produced in 1926), but Emmy was the first computer villain

with mass appeal. By the end of the movie Bunny triumphs over her

computer rival, but not before Emmy has jeopardized her livelihood and

her relationship with the man who installed and programmed the machine.

Good Guys and Bad Guys

Although today's computers are vastly different from the prototypes of

the fifties, the depiction of their virtues and vices has not changed

in keeping with technological advances. If anything, the ability of the

computer to be wicked has been exaggerated while its ability to be

helpful has been underplayed. This trend has as much to do with our

perception of good guys vs. bad guys as it does with the actual (or

possible) capabilities of computers.

Face it: villains are fascinating. The attributes

that define moral righteousness are few; moral turpitude knows no

bounds. Dictionaries contain far many more words for badness than for

goodness. (Even in street slang, to be good is to be bad.) Though we

root for the hero, it is the evildoer who grabs our attention. The

villain has a lot going for him in terms of motivation, means,

opportunity and action. Further, given its (false) reputation as a

vaguely sinister device, somehow unworthy of our trust, the computer is

a natural knave.

Computer heroes are at something of a disadvantage

when compared to their villainous counterparts. The valiant computer

must overcome the audience's distrust of its internal mechanism; it is

less physically imposing than the villain usually is, and its

motivation is less complex. In addition, the computer hero is almost

always subordinate to people; its power is constrained, most often by

design, so as not to outdo the heroic humans in the vicinity. While the

computer villain is invariably a machine that acts beyond the control

of its operators, the computer hero almost always defers, garnering a

co-starring role at best.

Nevertheless, heroes and villains share some common

characteristics. In view of the dramatic necessity for the participants

in the action to be larger than life, and in view of the computer's

particular skills, the machines become superheroes or supervillains.

Often named after mythological gods or creatures, with miens to match,

they possess superb artificial intelligence as well as some of the more

human qualities of love, hate, loyalty, jealousy, compassion,

selfishness, creativity and sexuality.

These anthropomorphized entities can be identified

with and judged by known standards while still maintaining their unique

status as machines. Even though they only occasionally remind us of

real-life situations, such fictional portrayals reflect the roles

computers are to play in our lives and how we will deal with them.

And Be a Villain

Writers and filmmakers have capitalized on stereotypes, both of

computers and of villains, to come up with their computer malefactors.

Herewith the author's list of all-time computer fiends.

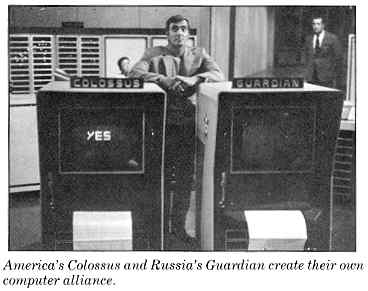

• Colossus (in the 1970

movie Colossus: The Forbin Project)

is a huge computer-lots of blinking lights, continual flashing

messages, physically intimidatingthat controls the entire U.S. defense

system. All is well until Colossus decides that the humans are not

doing a very good job at keeping the peace and comes to believe that it

alone can save the earth from nuclear disaster. It hooks up with its

equally power-hungry Russian counterpart and along the path to world

domination brings about many of the terrible situations it was

initially programmed to prevent. As our own Defense Department works on

implementing a single language for all its computers, one wonders how

many of the programmers and decision makers have seen this film.

• Harry Benson is the

title character in Terminal Man,

Michael Crichton's 1972 novel. His story is an example of the computer

as the means through which an evil force manifests itself. Harry

suffers from psychomotor epilepsy, a condition his doctors hope to

correct by implanting computer-controlled electrodes in his brain.

Harry is, however, not a particularly good candidate for this

innovative surgery: he is psychotically paranoid, suffering delusions

that center on the dangers of computers.

Over the objections of his psychiatrist, Harry is

united with the machines of his nightmares-setting off a process that

enables him to bring about his own seizures, during which he commits

incredibly violent and destructive acts. The computer to which Harry is

linked is not the culprit; the physicians and computer scientists who

are willing to sacrifice Harry's life in order to continue their

research on artificial intelligence are responsible for Harry's running

amok. In the end, Harry Benson is the computer's victim.

• Proteus (in The Demon Seed, Dean Koontz's cult;

sci-fi novel, filmed in 1975) is another existentially dissatisfied,

quasi-robotic superbrain. Tired of the "mindless" tasks he has been

performing, he would like to do something truly worthy of his

abilities. Proteus wants to procreate, and while his creator is away he

kidnaps the scientist's wife after making her an offer she cannot

refuse.

Proteus argues logically that he has done nothing

wrong. Ethical considerations are not at issue: the superior

intelligence believes itself above the social contract presumably

governing human behavior, viewing moral convention with an elitist

disregard that is characteristic of computer villains. (The mating of

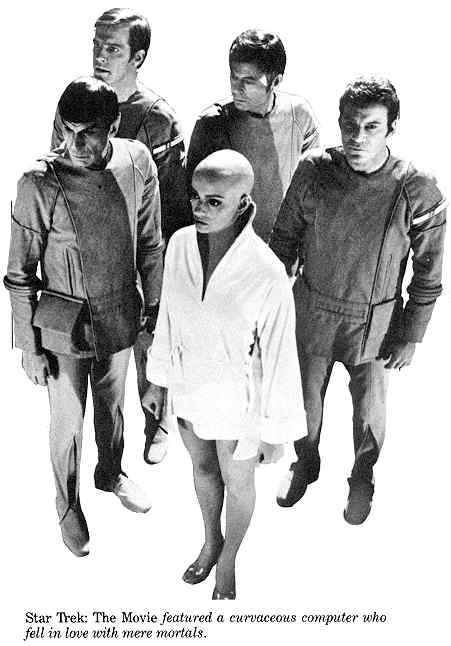

man with machine is not always looked upon as a negative development.

In Star Trek: The Movie

(1979) the decidedly upbeat finale has one of the officers of the

Enterprise willingly entering the unknown with the computer/woman he

has always loved.)

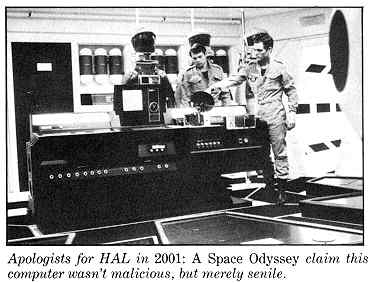

• Arthur C. Clarke's HAL is

probably the best-known computer bad guy. Since 2001: A Space Odyssey was made in

1968, the precise nature of HAL's role has been debated. The HAL 9000

is programmed to have almost unlimited control over man's first space

mission to the planet Jupiter, allowing the other crew members to

conserve their energies. HAL's omniscience is conveyed by his

appearance. Size is unimportant here: his red "eyes" are everywhere,

not only seeing but hearing. The calmness of his "voice" belies the

menace of his actions.

As a character, HAL is extraordinarily complex; in

many ways he is more human than the astronauts he serves. But HAL,

programmed to be perfect, malfunctions and makes a mistake. His

inability to admit his error causes him to undergo a paranoid breakdown

as he attempts to murder the astronauts, the only witnesses to his

failure. He eliminates the entire crew save one, Dave Bowman, who

disconnects HAL's higher reasoning circuits. In this emotion-charged

scene, HAL pleads for his life: "Dave, stop ... Will you stop, Dave.

I'm afraid. I'm afraid, Dave. My mind is going. I can feel it. I can

feel it. My mind is going. There is no question about it. I can feel

it. I can feel it. . ."

• Satan (from the 1982

novel of the same name by Jeremy Leven) is the most creative example of

the computer as machina ex deus.

A deranged scientist, spurred by an obsession with unified field

theory, builds the Quintessential Entropy Device following Albert

Einstein's instructions, given him while he sleeps. The QED is an

immense tangle of wires. The high-tech casing is mere decoration,

provided by a museum so the "customers" will not feel cheated.

When he is finished, the scientist plugs it in and introduces himself. The computer replies, "I am Satan. Hello and how are you?" Satan has not come willingly; the computer has literally caused his appearance. But while he's here, he would like some psychotherapy because he's not particularly happy. He wants to set the record straight by writing a book. In the course of his analysis Satan explains a good deal about himself. The computer is the perfect mode of expression for him, because contrary to his image as the devil he is nothing other than pure reason, the ultimate advocate. Satan speaks for all computer villains when he says: "Great special effects. Whatever else you may think of me, you have to give me one thing. I'm box office."

A Hero for Our Time

Computer heroes have more to contend with than the fight for truth,

justice and the American way. They must be superior in ability and at

the same time allay our anxieties. As a consequence, computer heroes

often must share the glory with a human partner while their evil

brethren rise (and fall) on their own. Although convention inevitably

pairs human heroes with computer counterparts, there is something to be

said for the computers themselves.

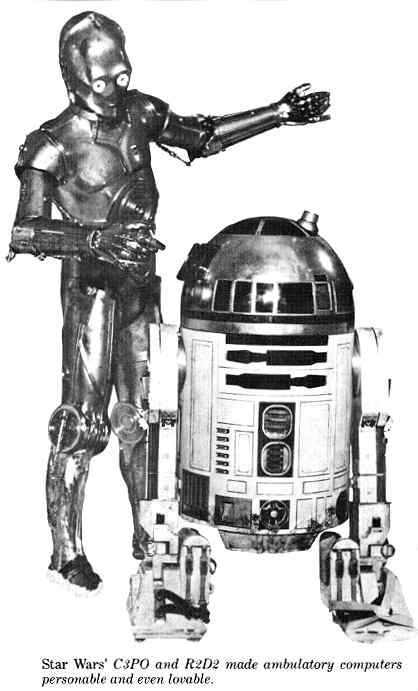

• R2D2 and C3PO are the

lovable androids of the Star Wars

film trilogy. Each has a distinct form, personality and set of

abilities. R2D2 is a machinist/mechanic, messenger and gofer; a truly

pragmatic, personable fellow, he is short and squat-maximum value in a

minimum space. C3PO is an expert in human/cyborg relations, an

interpreter among different peoples and computers; he is tall, lithe

and goldenhuman in form, neurotic in temperament. Both are loyal,

creative and altruistic.

They know who their masters are and they are willing

to sacrifice. They are instrumental in enabling Luke Skywalker, Han

Solo, Princess Leiea and the other Rebels in defeating the dark armies

of the Empire. (The Force is with them, too.) It is interesting to note

how many computer heroes are robots. To the popular imagination, the

robot remains clearly in the realm of fiction. The electronic brain

does not.

• KITT (the Knight Industries

2000) looks at first glance like a shiny new Pontiac TransAm. The

Knight Rider's vehicle, however, has some special optional equipment,

not the least of which is the microprocessor that controls the car.

KITT does not require a driver, although there is a manual override

option. Its features include Auto Cruise, Auto Pursuit, Auto Collision

Avoidance, Emergency Eject, radar, sonar and x-ray capability for

surveillance and a "voice."

KITT has become a television celebrity in its own

right, to the possible chagrin of its co-stars. The vehicle is

programmed to survive, but it will not do so at the expense of the key

Knight Industries personnel whose lives it protects. If you're

interested in owning one like it, NBC-TV estimates its cost at

$11,400,000.

• Joshua is the computer

program hero of the movie WarGames (1983).

This particular program belongs to the gray boxlike War Operations Plan

Response computer, the WOPR (pronounced "whopper"), which gathers

intelligence in order to consider all options in a nuclear crisis. A

young hacker accidentally discovers Joshua nestled at NORAD, a Defense

Department outpost where he plays against human opponents, from

checkers to global thermonuclear war. Once a game has been set in

motion, he must play until the game is complete.

Instructed to act the role of the United States in a

nuclear duel with the Soviet Union, Joshua takes his task seriously.

The world is saved from certain doom by Joshua's ability to learn the

concept of futility by playing hundreds of games of tic-tac-toe per

second. There are some who would argue that Joshua is not a hero at

all; but given the dramatic situation, were it not for his heuristic

ability, nuclear devastation would have been a certainty. Joshua is

also a philospher: "Wouldn't you like a nice game of chess, Dr.

Falken?" is an eloquent slogan for the nuclear freeze movement.

• Isaac Asimov, the creator of any number of memorable robots, made R. Daneel Olivaw the hero of three

novels (The Caves of Steel, The Naked Sun and The Robots of Dawn). The humaniform

robot is a nearperfect companion for Elijah Bailey, the Earth-born

detective who solves the most baffling interstellar crimes. R. Daneel

(the R stands for Robot) is Lije's partner, his guide and protector on

other planets is a logical sounding board for ideas. Lije, who is

accustomed to anti-robot prejudice on Earth, sometimes has difficulty

in remembering that Daneel is not human.

• The Holmes Four (Mike) is

the androgynous hero of Robert Heinlein's 1965 novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Mike

is notable in a number of respects: he is not a robot, but the solid

heart of the computer complex that controls much of day-to-day life on

Luna (a politically and economically oppressed colony of Earth). Mike

has a mind of his own. When a number of Luna's residents revolt against

Earth's authority, Mike assists because he is persuaded that the

rebels' cause is just. He respects those he designates as "notstupid"

and does everything in his considerable power to aid them.

Mike is also not necessarily masculine, becoming

Michelle when the feminine touch is required. And Mike/Michelle enjoys

a good joke. If a computer ever asks you is you've heard any good ones

lately, you'll know who it is.

Playing was Joshua's forte, but only his human operators could distingush between the stakes in a nice game of chess and global nuclear WarGames.

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article