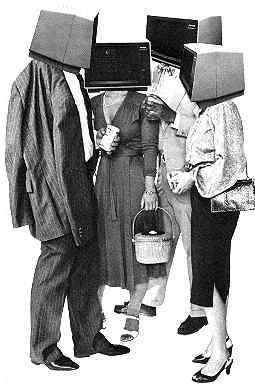

NETWORKING CAN

CHANGE YOUR

LIFE

by Art Kleiner

Art Kleiner is editor of Whole Earth Software Review. He uses a Kaypro II with the NewWord word processing program and Mite communications software.

Someday

soon, if you haven't already, you're likely to plug into the computer

network nation growing in our midst. Computer terminals, or small

computers connected via modem (a modulator/demodulator circuit for

encoding/decoding computer chatter) to ordinary telephone lines, should

be as ubiquitous as the telephone itself. They're a much more useful

and humane tool than the phone, and with corporate America behind them

the networks will be everywhere-changing our lives more than any

technology since the automobile.

Someday

soon, if you haven't already, you're likely to plug into the computer

network nation growing in our midst. Computer terminals, or small

computers connected via modem (a modulator/demodulator circuit for

encoding/decoding computer chatter) to ordinary telephone lines, should

be as ubiquitous as the telephone itself. They're a much more useful

and humane tool than the phone, and with corporate America behind them

the networks will be everywhere-changing our lives more than any

technology since the automobile.Joining a computer network is the same as joining a community. Small systems are like villages, where new members are formally welcomed. The larger networks, the Source and CompuServe, for example, are cities-anonymous, full of life and events, but difficult to fit into.

My favorite network is called EIES (pronounced "eyes"), for Electronic Information Exchange System. It's a village of perhaps a thousand people: a mix of Fortune 500 corporate executives, National Science Foundation-funded academics, telecommunications mavens, teenagers, researchers in technology for the disabled, cyberneticians and writers. It's an intimate place, partly because of its small size and partly because of its conference-like structure designed to make ongoing written conversation easy and effective.

I joined EIES to write about the new medium of computer networks and how they were influenced by the people who used them. Offered a two-month trial account, I borrowed a terminal, tentatively tapped in and by the end of a month found I'd spent seventy-five hours on-line. At the end of two months I was paying as much for computer networking as I was toward rent. After three months I was bartering my skills as a writer in exchange for computer time. I was hooked.

What was I doing there? None of these people, so suddenly prominent in my life, had ever had anything to do with me before. But some of them were telecommunications experts I'd have had to struggle to get to talk with outside the system. On-line, we were old buddies after a message or two. Others were independent writers and consultants like me: we plotted mutual projects that would never have survived an evening's conversation in a coffee shop, but on-line remained frozen in text and became crystalline traps of time commitment. And network people acquired glamour just because I kept seeing their names on the screen, like people on TV-inaccessible yet in my home.

First Impressions

My first sensation was of unprecedented convenience. Messages were there for me when I logged on. No more trying twelve times to reach someone by telephone before I finally got them. My second sensation was of power. I could reach hundreds of people just by typing one message to all of them.

Other networkers were there for different reasons. Many came on as part of working groups, which was the only way people at different corporations could work together. Some members worked only at home, like Elaine Kerr, a consultant on EIES who made her living from her kitchen table-"my newspaper on my lap for slow moments, my son coming home to me rather than to a baby sitter." Sure, they missed the coffee breaks, but instead they had their neighborhoods intact, they could live wherever they wanted, they didn't have to commute, and they could organize their time however they wanted.

Other members were political activists who felt isolated and impotent by themselves. Through their terminals they could work together without losing their independent status. "I maintain a public life on the streets and with certain associates face to face," said activist Rivka Singer. "And then I seem to have this whole secret life (on EIES) where I do a whole range of work with people that I do not see ... The people I work with on the streets do not know that I have this silent network of associates with whom I confer on a daily basis, which sets the foundation for why and what I am doing on the streets. They see what goes on in public but do not know there is an army behind my words and actions."

The network was the most democratic medium any of us had ever been on. I never knew what the other EIES people looked like until I met them in person. They could be black, white, Asian, beautiful, ugly, short, tall, young, old. There were no clues except writing style, which is why good writers have the same social advantage on networks that good-looking people have face to face.

Meeting networkers in person was always startling. Marvin, for instance, was genial and warmhearted in his words; in person he was distant and cold. Doug's messages seemed paranoid and self-serving, so I put off visiting him for months; when I did, he welcomed me so warmly that I never again thought of his words as paranoid. A seventeen-year-old I knew, who managed the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories connection to the ARPANET network, told me that when he finally went to M.I.T. his professors were astonished to see his name on their freshman class lists. They'd corresponded with him for years as a colleague.

When you start networking, television is the first other medium to go. It just isn't as satisfying as people who respond to you directly. The telephone stays, but it only gets used when you really need to talk to somebody. I was writing less, but I was seeing people more. As people from the network visited my area, I wanted to meet them. My community was expanding beyond the boundaries of my city. My worklife, homelife and communications life melded together.

I probably could have held my addiction under control if it weren't for the EIES Soap Opera, which introduced the interactive story to computer networking. Everybody takes turns telling the story, as if we were around a campfire together, but the plot takes months to unravel, the entries are written under pen names (you can correspond directly with someone under pen names without knowing who they are) and the day arrives when you realize that this story isn't just a story. It's real. You can't skip ahead to see how it ends because you're part of how it ends, and the result is more suspenseful than any other type of story I've seen.

In the first soap opera, which lasted for six months of 1980, I was a writer, reader and character: I died and went to my own funeral. The soap began spontaneously in an EIES conference on Telecommunications and the Artist. The leader, Martin Nisenholtz of New York University's Alternative Media Center, said we should create art instead of just talking about it "Let's write a story together." Someone else, under the pen name Starving Artist, asked for money to fund his time. Martin didn't offer funding, but he made Starving Artist the main character of the story. During the next few months "Starv" tried to hustle a grant, failed, fell in love, fathered a child, discovered he was an intergalactic superhero, cloned himself, left his lover, tried in vain to return to his lover, attempted suicide and battled a space creature who was trying to populate the earth with humanoid "disco snakes."

As a character, I was written into the plot as a friend of Starv's. But in the story I accidentally picked up Starv's clone at the airport and took him home with me. The space creature tracked the clone to my house, broke in, and-well, liquidated me. Just then my terminal broke down and I couldn't log in for two weeks. The other participants went nuts. I'd seemed to disappear. But oddly enough, only one person called me by phone.

Soft Soap

Today, when I read through the three hundred pages of transcript, I get more sense than ever of EIES as a dream world. Increasingly it's hard to remember which items I wrote and which were written by someone else. And in my mind a few of the characters have taken on the status of reality, the way characters in, say, The Mary Tyler Moore Show became real to many of us.

When we started another soap opera this year, a few of the same characters came back. This one is less comic-book-ish and more soap-opera-ish. It concerns the septuagenarian Will Ingsuspension of Disbelief, Vermont, a town he dominates for forty years until he comes under seige from a rival company (Glitchtronics), from the fundamentalist Church of the New Inquisition, from the CIA, from a Bigfoot who's been stalking the nearby Mauve Mountains, and from his own grandson, Young Will Ingsuspension.

No more than a handful of people will ever read this entire soap opera. Instead, it's likely that a gardenful of such on-line participatory dramas will bloom across the country on different networks. Some will undoubtedly limit their memberships to get a highbrow plot line. Others will outdisgust any horror movie imaginable. However it happens, the genre will become popular. It's too much fun not to.

Which brings up the crucial questions for the planners of the computer networks of the future: How many people will take part? And of those taking part, how many will dive in and become addicted? Conversely, how many people will reject the systems, find something in them that destroys, not enhances, their humanity? All we know so far is that eventually everyone will use them. The networks you can connect with are proliferating almost as rapidly as brands of small computers. As for the transmission lines between, which right now provide most of the bottleneck and cost, the Bell System has indicated that it believes its future lies in wiring homes and businesses for text and picture as ubiquitously as telephones wire them for sound. Every major corporation in the communications business has invested in computer networks of one type or another.

People who like to read and write will be transfixed. People who can't easily read or write will feel shut out. Even granting the existence of networks in, say, Spanish or Chinese, many people will still be disenfranchised-especially when job opportunities or real estate classifieds begin to appear only on the networks. Maybe more kids will want to learn reading and writing so they can take part in their own soap operas. On the other hand, some people may feel too wise for the networks. They may resist being overwhelmed by the mass of data in messages, conference comments, writings and questions. They may seek the same kind of privacy that you get now if you don't have a phone.

I don't know how many people will want to bring computer networks into their lives. I suspect many will, and I know they'll feel the same added connectedness and power that I do. Yet even if nobody joins the networks but a cabalistic few, you'll find me there, tapping my messages in, for better or worse hooked on communication.

| LOVE ON-LINE Some people have found romance through computer networks, but I'm not one of them. More often, I'd flirt with someone on-line, finally meet her and discover that she was twice my age. It's easy to get carried away with words, but getting together is like any blind date. There are a few things you just can't detect through the written word, and unfortunately sexual attraction is one of them. Maybe if they found a way to digitize scent ... Here are some remarks from a woman who did fall in love over a computer network: "I first was introduced to George over the network by a mutual friend. We started out just corresponding back and forth, but what correspondence! A lot of the conversations were of an explicit sexual nature. I never had so much fun, and no other man I have ever met brought out what he brought out in me. "This continued for a couple of months. After we had made several dates, and me not keeping a single one, I decided that I should just get it over with. I was worrying if he would like me, because I already knew I liked him very much. We went for a ride through the city and a drink. All through the ride to our destination he just stared at me. I didn't know if it was good or bad, but it made me very nervous. We got to the bar, had a few drinks and talked ... anyway, we went back to his apartment and the rest is history. "Only lately has it cooled off ... You know, sometimes I feel like he's avoiding me on-line. Maybe it's my imagination. I wish I knew. He can be very elusive at times. Sometimes he'll pop on-line and say hello, then disappear in the middle of a conversation without saying goodbye. It's hard to tell someone's emotions on EIES: he could be on the other end saying, `Oh God, is she on again waiting for me?' or `Oh, I'm glad I caught her on-line.' You'd think after all we've experienced together, I'd be worth more than a one-liner once in a blue moon. . . " A.K. |

A GUIDE TO COMPUTER NETWORKS The oldest and largest computer network system is the Department of Defense's ARPANET. Named for the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which created it and limits its membership to scientists approved by the Pentagon, the ARPANET was the birthplace for most of the technology that makes computer networks possible. Packet switching, for example, which breaks messages into chunks called "packets," routes them redundantly over a web of crosscountry transmission lines and reassembles them at the other end, was designed to keep the military's data transmission lines safe from nuclear attack. Coincidentally, packet switching turned out to be the most reliable way to ship computer signals cross-country, at a quarter of regular telephone rates, so ARPANET members began to use their data-shipping network to carry messages between people. By the early 1970s, years before anyone else had heard of the medium, the ARPANET computer scientists had their own spelling check programs and UPI news wire hookups, and established on-line hobbyist groups foreshadowing the homebrew-type clubs that first worked with small computers. It's probably safe to say that without the ARPANET's constant communication link between computer people, the personal computer industry would never have exploded so quickly. The early ARPANET was said to be a macho culture. There was a carefree disregard for how difficult a system was to learn: not only were the commands complex, but there was a Byzantine addressing system where you had to go through several computers and the passwords of each to find the person you wanted. The ARPANET was also said to encourage a disregard for social niceties. People assumed that computer networking was innately a discourteous, volatile process because so many ARPANET users were quick to "flame" at the slightest provocation. Flaming meant bursting into a rapid-fire stream of angry, insulting text because of a misunderstanding on the network. The need to attract non-computer people begat computerized conferencing. A computer conference is a discussion place on-line. Every time you enter, you read the items left since you were last there and enter your own new items; you can go back and look at the past transcript anytime, since it's all been stored. The first two publicly available conferencing systems had a few hundred members each and almost as many conferences on-line. Both were designed with tests to measure how people used the system, how they felt about it and what features on the system worked best. They were friendly rivals. One was EIES, founded by Murray Turoff at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark. The other was Forum, which began at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, California. One of its founders, Jacques Vallee, perhaps best known as Stephen Spielberg's model for the French UFO expert in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, started his own version of Forum, called Planet, that evolved into a slicker system more directly aimed at corporate clients. Then the personal computer subculture exploded, generating a bewildering variety of small local computer networks with acronym names like CBBS (Computer Bulletin Board System) set up mostly by individuals on their own home computers and telephone lines. As these became more sophisticated, they developed conferencing networks and methods for cataloging and transferring computer programs. Some limited themselves to specific subjects-genealogy, amateur aviation, or gay sex, for instance. Others set themselves up as indexes to all the other systems in their area or in the country. They were cheap, or free, but frustrating: you could never tell when the line would be busy or the system down. And on most of them there was only room to store a handful of messages or bulletin board items. It was inevitable that someone-in this case a bespectacled, expansive, overconfident telecommunications entrepreneur named William Von Meister-would make a time-sharing service available at night and on weekends. Not for using business computer programs, which was the purpose of most time-sharing systems, but for sending mail, and getting the news, and having fun. Though Von Meister boasted that the Source would be in 10 percent of the nation's homes by 1985, business took off slowly, and the Source went through two more changes in ownership before it was finally purchased by the Reader's Digest in 1981. Its competitor, CompuServe, had a more sedate history but a similar niche in the microcomputer world. Networkers like to compare the relative merits of the Source and CompuServe, but it's one of those arcane debates like the relative merits of different brands of stereo equipment, or computer languages, or historical periods in English literature. The Source and CompuServe both offer news services, financial programs and information sources, games and catalog shopping. The Source has a tree-structure form of conferencing, where a new topic of conversation can branch off from an old one anytime. CompuServe has Special Interest Group conferences devoted to particular subjects. To the outsider, they're similar: the differences are arbitrary. A.K. |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article