MAGAZINE

MADNESS

by Stan Veit

Personal computer magazines are among the most profuse offspring of the microcomputer era. To fill the information vacuum left by poorly written manuals and uninformed salespeople, the computer magazines have increased with rabbit-like speed. At last count there were some 450 titles to choose from, up from just two magazines in 1975. Dispensing solid technical advice and futuristic hearsay, they have begun to take over the newsstands, pushing the hairdo and biker magazines out of the way and causing more than a few hernias with their thick, ad-laden issues.

As in the rest of the burgeoning personal computer industry, what were once amateur efforts produced on kitchen tables and playroom floors are now slick sources of huge revenues. The pioneering efforts have been absorbed by large conglomerates and the quest for profits has given rise to several publishing empires, all based on the advent of the microprocessor. And in their wake the magazines have generated more than their share of controversy.

Pioneering Periodicals

In the beginning, there was Creative Computing, published and edited by Dave Ahl, and Byte, published by Wayne Green and edited by Carl Helmers. Originally, Creative Computing was addressed to the few educators who had access to their school computers; these were minis or mainframe machines-not microcomputers, which hardly existed in those dark ages. The other magazine, Byte, had been founded for the computer hardware and software hobbyists who were just starting to emerge.

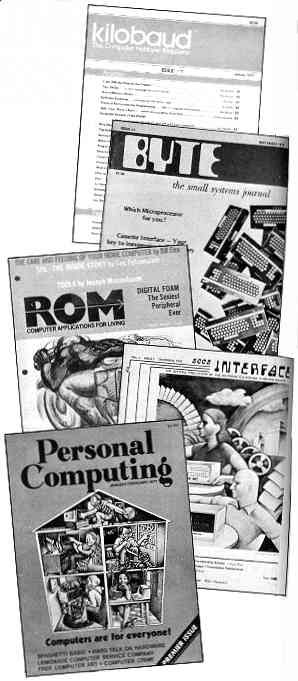

Premier publications: first issues of

early computer monthlies led to the largest number of magazine titles

ever published on a single subject.

Wayne Green, the publisher of 73 magazine for "ham"

radio operators, felt there was a market for a periodical devoted to

hobby computing and small systems. Carl Helmers had been editor of one

of the "little magazines" on hobby computers, and Wayne selected him as

editor of his own project. Both of them worked day and night to get out

the new magazine, and in September 1975, Volume 1, #1 of Byte: The Small Systems Journal

appeared. It was an instant success because of the huge latent audience

of electronics hobbyists and programmers who wanted to know more about

the little computers you could build and operate yourself.

Because he was in the middle of an IRS audit and did

not wish to have his new venture involved, Wayne registered the

magazine in his wife's name. As it turned out, this was a serious

error. No one except those involved will ever know just what happened,

but when the smoke cleared Wayne still had 73 magazine and his ex-wife,

now married to a German gentleman, had Byte, with Carl Helmers as the

editor.

Virginia Green (nee Londoner) later divorced her

husband Manfred, sold out to McGraw-Hill and as Virginia Londoner

became a very rich lady. Wayne went on to found his own large group of

computer magazines, including Kilobaud

and 80 Microcomputing.

He eventually sold his company to Pat McGovern of CW Communications

Inc. for sixty megabucks! The rift between the Londoner and Green

publications, though no longer owned by their originators, has left its

mark on the town of Peterborough, New Hampshire, the computer magazine

capital of the universe. Among the legendary incidents in the ongoing

feud: Wayne Green's fluorescent-lit sign that proclaimed "Merry

Christmas To All-But One."

What happened to Creative

Computing? Well, David Ahl, its founder, worked hard at the

full-time job of making his magazine successful. He also bought out

numerous small magazines that didn't make it, and got into a position

of having to print many, many more copies than he was being paid for.

He, too, looked for a buyer and found one in the Ziff-Davis

Corporation. Both Wayne Green and David Ahl had become synonymous with

their publications and continued to write for them, setting a warm

personal tone in contrast to the hard-core technical bent of Byte.

The third oldest computer magazine, Interface Age, also had a stormy

birth. Starting out as the newsletter of the first successful national

computer club, the Southern California Computer Society (SCCS), then

changing its name to Interface,

it was staffed by volunteers before it became Interface Age under publisher Bob

Jones and began focusing on business computing. SCCS itself was a

victim of "Col. Whitney," a swindler who absconded with thousands of

dollars invested in its group purchase plan; in the end, the club was

destroyed by the lawsuits that ensued.

One of the victims of early computer magazine

madness was Erik Sandberg-Diment, a feature writer for the New York

Times. Having contracted the computer bug in a New York computer store,

Erik decided to jump in and publish another magazine called ROM. Although he hired some of the

best writers in the industry (including Joseph Weizenbaum of Eliza fame

and the ubiquitous Adam Osborne), the market was still too small to

support another magazine and ROM

perished for lack of the capital needed to hold on for just a little

longer. The same thing happened to Microtrek and some other early

magazines.

| HOW TO READ A COMPUTER MAGAZINE Before you get into the computer magazine habit, sign up at your local gym or health club and get in shape. You'll need all your strength to lift and lug a magazine that's two inches thick with computer ads.

THE FLASH |

| THE 10 ESSENTIAL COMPUTER BOOKS Market studies show that people who buy personal computers are likely to buy ten books on the subject within the first year. In place of all those programming guides that go unopened and gussied-up instruction sheets with less literary merit than a toaster manual, the books below deserve your attention.

|

Sing the Computer Specific

Two events changed the computer magazine business so that it would never be the same again. One was the advent of the Apple II; the other was the growth in popularity of the Radio Shack TRS-80. These computers brought thousands of new users into the field, but their interest was in Apples or TRS-80s and nothing else-except software or peripherals for their machines.

Again Wayne Green pioneered, this time with the first machine-specific magazine, 80 Microcomputing, devoted to the Radio Shack TRS-80. Quickly it became almost as full of advertising as Byte, and its circulation climbed as more and more TRS-80 computers were sold. Other machine-specific magazines were then published for Apple, Atari and Texas Instruments computers.

When IBM entered the market with the IBM PC, a new wave started. David Bunnell, editor of the Altair house magazine Computer Notes, had come out with Personal Computing, but nothing seemed to go right for him. Personal Computing, after being sold several times and ending up in the Hayden Publishing stable, went on to become one of the most popular computer magazines. Then Bunnell got the idea of starting a machine-specific magazine devoted to the IBM PC. To this end, he assembled a staff of very talented people on the West Coast. There was one thing lacking, however, and that was the capital needed to start the magazine, so he began to look around for someone to back him.

Lifeboat Associates, one of the big success stories of the microcomputer industry, had grown to be the largest supplier of CP/M-based business software. Investors had just bought out its original founders and had installed Dr. Ed Currie as president of the company. Ed was a friend of David Bunnell (the two had worked together at MITS), and when David asked him for capital he suggested Tony Gold, one of the Lifeboat founders, as a source. The Tony Gold and David Bunnell combination seemed to click, and Tony agreed to put up the money for the new magazine.

Here again the story becomes obscured by its many versions (may the courts alone have to decide!). One fact is known to all: PC magazine was a huge success. Since a whole industry was created to supply software, peripherals and expansions for the IBM PC, and every company in the PC industry wanted to advertise in PC, the magazine grew thicker with every issue.

Behind the Scenes

Most people don't realize that magazine publishing is a highly capital-intensive industry (perhaps the reason so many magazines start and disappear in a few issues). You have to pay the printer, the paper company and the staff as you go. The U.S. Postal Service must be paid before one copy is mailed. The cost of selling subscriptions is high and soliciting ads is expensive; advertisers take thirty to ninety days to pay you, and the cash flow problems are only for the brave and the rich.

These conditions caused problems for PC magazine. Tony Gold lacked the kind of capital necessary to keep expanding at the rate the magazine was growing, and the solution was to sell out to one of the huge magazine or communications corporations. It was now computer time, and they all wanted to buy PC. The question was, which suitor would it be?

Of the prospective buyers Bunnell and staff had come to favor Pat McGovern and his CW Communications Inc., which published Computerworld, InfoWorld and several newspapers in the computer field. Tony Gold seemed to lean toward the giant Ziff-Davis, which had recently purchased David Ahl's mini empire. To make matters worse, Bunnell believed that he and his staff had been promised 40 percent of the magazine. Gold said this applied to profits, not ownership. No stock had been transferred to anyone but Tony Gold.

Relations at PC became strained, to say the least, and the entire staff threatened to walk out. Tony Gold as sole owner sold out to Ziff-Davis, and despite liberal salary and job offers the staff quit as a group to start a new magazine, PC World, which overnight grew as thick as PC. The beneficiary of this move was Pat McGovern and company. The loyalists who left with David to start PC World have quickly raised it to one of the best sellers in the personal computer field.

Incidentally, PC has not suffered under ZiffDavis management; it put out the largest single issue of any consumer magazine ever published-surpassing Vogue-and has expanded into PC-related publications with an IBM magazine on disk, an IBM technical journal and an IBM weekly.

When a reader tries to select a computer magazine from a wall full of similar publications, the choice gets harder and harder. And still new magazines are announced every day. It's easy to predict a shakeout, with many computer magazines perishing in the years to come, but no one is smart enough to know which ones will survive and which ones won't make it into the next generation-or how long computer magazine madness can go on.

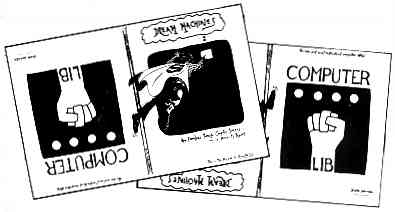

| WHY I WROTE THE FIRST PERSONAL COMPUTER BOOK In 1974 I was indignant about the stereotype of computers-big, bureaucratic, "scientific," and widely believed to be the rightful province of IBM. What was particularly galling about this stereotype was that at the time IBM was literally the enemy of personal freedom with the computer. When I wrote Computer Lib, personal computers were still the province of $50,000 DEC minicomputers and their imitators. Thus I sought to create a best seller and reach the masses with the True Word on the fun, excitement and personal challenge of the computer. Though I sold over 40,000 copies of the book I self-published (and laid the groundwork for the computer book publishing industry in the process), this did not work. The people who read Computer Lib were brilliant eccentrics. Definitely not the masses, but still a very neat constituency. The True Word eventually got out. I'd say most people have an inkling of it by now. I wrote for the simple ideal of freedom: the shortterm freedom of people to do their own thing with computers, a flower that was about to open, and the much deeper sense of freedom that has to do with long-term political issues. Though I tried, these issues haven't yet penetrated the public mind. I also wrote the first personal computer book for the sake of my personal freedom, to make a lot of money from it and not have to take God-awful jobs anymore so I could work on the writings and projects I consider important. This did not work, either. It was my own fault for making the print too small, which turned out to be an irrevocable decision because I pasted the mechanicals down too hard. (I didn't believe, being then in my thirties, that other people really had trouble reading fine print. Now I know. Ah, well.) Finally, I wrote Computer Lib as an invitation to smart young hackers to join me in my great crusade, Project Xanadu, now a special form of storage and eventually to be the electronic library for those who love ideas and freedom in all their richness. The invitation was mischievously-nay, perversely-hidden in the back of the book, which was in turn hidden in the middle. This assured that only the most persistent and brilliant readers would find it. But this was the part that worked! Directly or indirectly, the book brought in mad geniuses and wonderful people who built on my designs, made the mathematical underpinnings serious and robust, and allowed Xanadu to be born.  Ted Nelson published his binary book with a pair of covers for sections printed back to back and upside down: Computer Lib, his personal computer manifesto, and Dream Machines, a visionary exploration of graphics. TED NELSON |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article