CREATIVE PLAY

by Nolan Bushnell

Nolan Bushnell is the founder of Atari, Inc., and Androbot, Inc. His current brainchild is Catalyst Technologies, an incubator for high-tech start-up firms.

The computer, the single most powerful development of the twentieth century, is still puny in comparison to the mind of man. The difference lies in the innate creativity that is our birthright, our passport and our guide through life, without which we would be little more than machines executing programs someone else has written. The goal in producing computer-programmed video games is to provide the stimulus, the opportunity, for people to experience the essential creativity they knew as children, when their minds were actively involved in fantasy worlds of their own making. We have discovered that computers can be a highly effective tool in inspiring people to draw upon this often repressed reservoir. One way we achieve this is by designing games that combine fantasy with problem solving.

Problem solving is closely linked to creativity

because it involves hypothesizing, or making guesses. In order to solve

puzzles, you have to invent solutions and then try them out to see if

they'll work. Whether it's a crossword puzzle, detective story, board

game or video game, you're confronted with a problem that can be solved

only if you devise a viable algorithm. In computer parlance an

algorithm is a procedure for solving a mathematical problem in a finite

series of steps, but I use the term to refer to the step-by-step

procedure for accomplishing any kind of objective or solving any kind

of problem.

You break the problem down into basic component

parts. You prioritize the areas needing attention. Then you formulate a

strategy to solve the problem. Sherlock Holmes, a keen observer who

deduced most of his solutions by creative hypothesis-building, is an

example of someone who utilized algorithms. Holmes noted all the minute

details of his environment, methodically proceeding to create

hypotheses in such a way that all the data were met, and only then did

he offer his solutions.

Deciding on a strategy, therefore, can be a very

creative act. And watching how the strategy you create with your own

mind turns out-that's really what the fun is all about.

After all, who knows whether your strategy will win

or lose? The only way you're going to learn is by devising new

strategies and testing them whether they work or not.

Video games have a unique educational component that

involves the application of an algorithmic process to a certain kind of

problem. In this case, the player faces the challenge of eye-hand

coordination applied algorithmically to solve a problem in motion

graphics. For instance, how does a person learn a pattern by which he

scores high at Pac-Man? He must constantly test his hypothesis. If the

hypothesis doesn't work, the feedback of the medium is quick and final:

his quarter's gone.

The learning process, then, is one of constantly

testing your hypotheses to see which ones work, which ones don't. In

the process a person can assimilate one of the basic rules of

scientific discipline, though I think this kind of learning often

happens at a level of mind that you may not be totally aware of.

Research has shown there are important educational

components associated with playing video games, and these special

benefits accrue from the tests of eye-hand coordination comprising the

fundamental challenge of virtually all video games. The development of

good eye-hand coordination is particularly important in young children,

who need to develop a sense of confidence and a feeling of mastery over

their environment. Moreover, playing video games not only results in

improved eye-hand coordination, but also-fascinatingly

enough-correlates highly with an improvement in reading skills. If I

were to offer a creative hypothesis on this phenomenon, I would guess

the definitive skill involved probably has a lot to do with youngsters

learning to focus their eyes, to scan data by tracking movement on a

screen.

On the other hand, I wouldn't claim that all video

games are educational in and of themselves. As in other media and other

art forms, there are so many different types that it is impossible to

treat them as a monolithic group. Certain video games give knowledge of

some scientific principles, while others actually violate the same

principles. Some games appear to reward the player for activity that

would generally be interpreted to be rather antisocial behavior.

But I don't need to defend video games per se,

because as in any other medium there are good ones and bad ones. The

moral dilemma that some adults toss themselves into over the issue of

video games seems similar to the hue and cry raised in opposition to

that allegedly corruptive new medium introduced at the turn of the

century: motion pictures. As is true of the movies, a great deal

depends on the character of the producer as well as the eye of the

beholder. You can't let a few rotten apples spoil the whole industry.

Video games are clearly here to stay. The only

question is, what form will they take in the future? Like most other

entertainment fields, the future of video games will be bounded only by

the imagination of the people in the production arena.

I believe that video games will proceed

unrelentingly toward higher-resolution, higher-definition and more

intricate graphics. Some of the technologies that will contribute to

these improvements are higher-speed microprocessors, cheaper memory and

laser optical video disks.

As home video games improve, arcade video games will

take on more mechanical aspects to provide the player with an enhanced

experience, one that will increasingly blur the distinction between

internal and external perceptions of reality. I think games in arcades

will become more elaborate as arcades themselves evolve into mini

amusement parks from their present incarnations as rooms full of

television sets with coin slots on their fronts.

As competition for home video games, I envisage

arcade games involving all the human senses in the game-playing

experience. We've seen a trend in which sound systems have improved

enormously. We already have capabilities to chemically synthesize a

variety of fragrances. Soon game machines will be able to vibrate,

bringing in the tactile sense. And, utilizing advanced locomotive

devices, we'll start moving people around bodily from scene to scene.

I don't know at this juncture exactly how we'll be

able to get taste in there, but I never say never. And I always avoid

always. We're working on ways to trigger different brain receptors that

are responsive to taste perception. I believe there will be ways we can

fool a person into thinking he's experienced taste.

The overall objective of engaging all the human

senses will be to create a heightened sense of realism. The game

designer who enhances the fantasy-who makes it more real-will be the

one who is the most profitable. Look at it this way: if you can have a

video game designed to simulate a trip to Europe for twenty-five cents

a throw, and you think playing a video game is as real as getting on an

airplane and actually going to Europe, well, who's to say a trip abroad

is preferable when you can have all that fun at a local video arcade

for so much less?

Of course, the price for this enhanced experience

will probably go up a bit. But this is inevitable as long as people

demand more capabilities. Even so, you'll get much more back in terms

of realism for your expense, because that never-ending march toward

realism will continue.

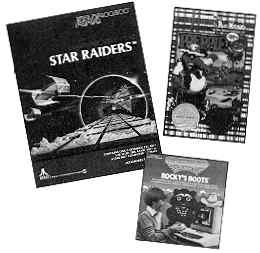

THE MASTERPIECES In the space of less than five years, games for personal computers have been transformed from an oddity to a major industry. The consumers of 1979 had to take what was offered; now their biggest problem is choosing the best from a bewildering array of software. Below is my own list of masterpieces. • Star Raiders. The appeal of this game arises from its combination of engrossing qualities. First, the fantasy of dueling in space is far better supported in Star Raiders than in any other similar game. The stars move believably; the graphics look real (I've seen people duck trying to avoid an incoming photon torpedo). The sounds are also right: the engines roar, the explosions crash, and photon torpedoes zing with impressive reverberations. And the array of instrumentation available to the player reinforces the fantasy that he is at the controls of a complex and powerful spaceship. Second, as the player advances in the game, the fantasy world becomes more intricate. Enemies must be hunted down, equipment must be repaired at starbases, energy must be conserved. Even experienced players can continue to make discoveries for many, many hours of play. • Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. This is the classic fantasy role playing game. It has excellent graphics, which are put to effective use rather than treated merely as window dressing. The sound is imaginative and informative, complementing the graphics without distracting. The game sports an interesting set of problems without annihilating the less experienced player, and the world it creates is rich, colorful and believable. What more can one ask of a game? • Preppie. A straightforward implementation of Frogger, this game deserves praise not for its design but for its magnificent implementation. The graphics are very good in the sense that they support the cute theme of the game. The little player shuffles along in a most comical fashion. If he is run over, he stretches out in a slapstick representation of being squashed. But what makes Preppie stand out is its music. Delightful little melodies trip along during the course of the game, and even the funeral dirge that accompanies the player's demise sounds like it should come from a calliope. • Rocky's Boots. This is one of the out-and-out masterpieces that entirely redefine what computer games can be. Rocky's Boots is a game about digital logic and is without doubt the most impressive educational game yet created. Its simple, clever graphics system allows the player to build a staggering variety of logical circuits and explore their behavior. One can actually see the "electricity" moving through the circuits (it's orange). This game shatters the positions of skeptics who doubt that computer games will ever have educational value. CHRIS CRAWFORD, author of the strategic game classic Eastern Front 1941 and manager for games research at Atari |

Return to Table of Contents | Previous Article | Next Article